Introduction

TRANSDISCIPLINE HAS BECOME a paradigm towards which all academic research systems

shall evolve, considering that our complex socio-environmental problems require new

knowledge production approaches to understand these phenomena and provide clearer

and more comprehensive alternative solutions. Today, socio-environmental transformations

occur at global scales, albeit with particular characteristics in each territorial

context.

This paper analyzes the experience of a research group working in Yucatan, Mexico,

seeking the joint production of knowledge about sustainable housing to address precarious

households in the outskirts of Merida, the capital city of the state of Yucatan. This

city enjoys a positive image at national and international levels, supported by high

safety and quality-of-life indices (Bolio 2014). As a result, immigration has increased, leading to accelerated urban growth that

has boosted housing construction projects. This phenomenon has influenced in the increase

of land, construction, and real estate prices (Combaluzier 2021).

At the same time, Merida also experienced decades of immigration of rural populations

into the city in search of better job opportunities and urban services. Some of these

groups settled in periurban areas of southern Merida, where communities have faced

difficulties buying their own houses, in addition to household overcrowding and self-construction,

frequently unfinished. In turn, the city has historically experienced a high socio-spatial

segregation where the northern zone enjoys important privileges while the southern

one has been relegated (López 2019).

Within this framework, in December 2020, the research group undertook a project to

seek sustainable housing solutions in Merida, Yucatan, through technological innovations,

submitting it to the National Council of Science and Technology (Conacyt, in Spanish),

the agency of the Mexican federal government in charge of scientific and technological

development.1 It is worth noting that the current federal government has sought to focus the research

agenda on environmental sustainability issues, aimed at addressing social needs and

national problems. This led to the formation of an inter and transdisciplinary team

involving different academic institutions, local government agencies, civil society

organizations, citizen groups, and social-based organizations living on the periphery

of the city.

The present work analyzes the achievements in the work team multisectoral conformation

and the obstacles and limitations faced during this experience. It is important to

point out that this is not a research paper, but rather a narrative, critical and

reflective process based on the experience of the authors as participants in an inter

and transdisciplinary research group, with the purpose of contributing empirically

to the analysis of the implications of these methods for the production of new knowledge

and the solution of concrete problems, as in the case of sustainable social housing.

The paper begins with a conceptual review of sustainable housing and inter and transdisciplinary

research. It then discusses the new orientations that are being given in the federal

scientific and technological policy. Subsequently, the local context in which the

studied project was carried out is analyzed, as a prelude to the presentation of the

experience studied and the analysis of the challenges that arose in the development

of the research, in the new policy framework, especially regarding the dialogue between

participants from different disciplinary fields and diverse social sectors. Next,

the involvement of the communities of the peripheral areas of Merida, Yucatan in the

project is addressed, particularly through the development of participatory workshops.

Finally, reflections from the analysis of this experience are presented.

About the notion of sustainable housing

Housing is the most intimate space of the humans who inhabit it and although from

an administrative perspective it is a habitable material space, it also reflects sensitive

spaces of the way of life, cultural identities, family needs and climatic conditions,

representing the complexity of social relations that must be satisfied (García 2021). While for some privileged social groups, it is a reflection of aesthetic styles

and preferences, for the most vulnerable groups it is a result of their economic possibilities

and limitations (Canché et al. 2024). Therefore, the issue of housing needs to be approached from different disciplinary

approaches, such as architecture, urban planning, engineering, sociology, political

science, environmental science and anthropology, to mention a few; which is a reference

for the inter and transdisciplinary approach of the team formed for sustainable housing

in periurban areas of Merida, which is analyzed in this paper.

Housing is a basic right, as enshrined in Article 4 of the Mexican Constitution, according

to which “every family has the right to enjoy decent and dignified housing”. However,

the housing of vulnerable populations represent different problems such as the insecurity

of the materials with which they are made, overcrowding, lack of public water, sanitation

or electricity services, and even their settlement in unsafe or at-risk areas (Canché et al. 2024). Moreover, in many cases these social groups do not enjoy security or property certainty,

having to improvise their homes in precarious conditions, many in rented or other

relatives’ homes, or in unfinished projects, all of which deteriorate their quality

of life (Cruz et al. 2024). It is considered that in Latin America these scenarios are faced by popular settlements

that constitute 60 to 70% of urban areas (Fidel and Romero 2017).

Thinking about the habitability of housing in contemporary societies also requires

considering sustainability. This is an essential factor if we consider that the increased

urbanization processes have contributed significantly to aspects such as the fragmentation

of ecosystems, changes in land use, reduction of fo- rest areas and many other socio-environmental

impacts that entail risks for cu- rrent and future populations, which increase in

vulnerable areas. It is therefore necessary to consider sustainability criteria in

low-income housing throughout the entire life cycle of the building, from design,

construction and operation to its destruction (Solís, Robles and Rodríguez 2020).

Sustainable housing has been conceived from different perspectives that include the

architectural -use of efficient life and long useful life of the building-, and the

institutional quality of housing and the environment that favor the responsibility

of neighbors with their community (González-Yñigo and Méndez-Ramírez, 2018). Therefore, from this second point of view, in Mexico, sustainable housing, in addition

to considering environmentally friendly criteria, links a sustainable operation in

terms of energy and water saving, for which the incorporation of eco-technologies

is required (Infonavit [2010] cited in González-Yñigo and Méndez-Ramírez, 2018), such as solar cells or wastewater treatment plants.

Fidel and Romero (2017) specify that the use of ecotechnologies in the design and construction of housing

requires a participatory approach, where the knowledge and perspectives of the populations

involved are integrated to the specialized technical knowledge. Experience has shown

that participatory processes generate more solidarity and commitment among inhabitants,

allowing a greater collective appropriation of spaces, as opposed to planned real

estate projects, many of which have an industrialized and unsustainable production.

In short, the interaction between multiple knowledges can lead to better solutions,

overcoming the problems generated by a technocratic vision of housing (Fidel and Romero 2017), a line that was also traced in the call from which the project analyzed in this

paper arose.

In this tenor, some factors of sustainable housing referred to in this topic’s literature

include the materials used for construction, which generate the lowest possible environmental

cost, systems for the rational consumption of water and energy, natural ventilation

and lighting, optimization of living space and even the reuse of materials at the

end of their useful life (Mingüer 2017). Sustainable housing also involves overcoming the anthropocentric vision that governs

the idea that humans can take over any territory and adapt it to our needs and tastes,

including other criteria related to the reduction of ecological impacts in the transformation

of natural spaces (Mingüer 2017).

In line with the above, the call to which this project subscribed stated that “one

of the particular objectives of Conacyt in terms of research on sustainable housing

and cultural and environmental relevance [...] is to promote the formation of interdisciplinary,

inter-institutional and cross-sectoral research and advocacy groups that understand,

in their complexity, the fundamental problems of housing and, in general, of habitat”

(Conacyt 2020a). To this end, it motivated the enunciation of proposals aligned with SDG 11 that

included, among other aspects, approaches to climate change mitigation; buildings

resilient to disaster risks and public health; collaborative innovations for the development

of technological systems; optimization of the life cycle of housing from a circular

pers- pective; articulation to the regional vision of adequate housing and sustainable

cities; and housing as a mechanism for food security and sovereignty (Conacyt 2020b).

In the project analyzed here, particular aspects of sustainability in housing were

considered in the context of the subtropical climatic environment of a city like Merida,

where high temperatures and humidity conditions remain throughout the year. Therefore,

some sustainable strategies contemplated the design of environments with cross ventilation,

which allows regulating the high temperatures of the environment, the generation of

shadows to prevent overheating, a greater use of vegetation (trees or green walls)

and design of roofs and walls that provide shade (Canché et al. 2024). Another crucial aspect was the development and use of ecological materials to replace

more traditional cement-based materials, and the replacement of natural wood with

plastic or composite plastic wood, in order to reduce deforestation, allowing the

use of other natural fibers whose residues can be reused (e.g., agave bagasse, sugarcane,

rice husks, etc.) (Canché et al. 2024).

Semblance of inter and transdiscipline as approaches to socioenvironmental research

The inter and transdiscipline concepts are closely related to the sustainability challenges

emerging over several decades to preserve life on Earth. These imply understanding

highly complex (Morin 1990; García 2006) and dynamic socio-environmental issues, which remain permanently uncertain (Funtowicz and Ravetz 1999). Both inter and transdiscipline stem from new configurations of academic research

teams that require expanding their own epistemological conceptions to achieve a greater

impact on the transformation of reality (Giraldo and Arancibia 2023).

Various disciplines come into contact in interdisciplinary research, modifying their

methodological structures and leading to interdependency, ultimately resulting in

the integration and enrichment of knowledge (Torres 2000). It should be noted that work teams include specialists from different fields of

knowledge and disciplines, meaning that interdisciplinarity is a characteristic of

research processes rather than work teams, which are multidisciplinary.

Transdiscipline is considered a higher stage of interdisciplinarity (Delgado 2019), where it is essential to include various population interests and values (Klein 2008) to influence the transformation of socio-environmental problems. This involves the

need to incorporate non-scientific knowledge provided by different social stakeholders,

which contribute, from diverse experiences, perspectives, and worldviews, to understanding

complex issues within specific territorial scenarios.

The above means that transdiscipline is needed for both theoretical and practical

perspectives (Luengo 2012), which implies the impact on the design of better public policies and the collaboration

with various social actors to solve a specific issue. Consequently, in transdiscipline,

methodological and theoretical boundaries fade away to integrate practical, technical,

or traditional knowledge through intercultural dialogue to produce a novel knowledge

system about a phenomenon that science itself could not totally explain or solve on

its own (Delgado 2019; Luengo 2009).

One approach to undertake transdisciplinary work is through Participatory Action Research

(IAP, in Spanish), which contributes to social change as it can potentially increase

the influence of participants to promote this transformation. It can also foster the

development of the community involved, promote leaders, solve issues according to

their priority, stimulate self-help, and strengthen solidarity and collaboration among

community members (Balcázar 2003).

In practice, thinking about transdiscipline implies an aspiration rather than an attained

goal and entails a paradigmatic revolution. This approach will require a gradual change

in the traditional way of organizing academic communities and improving communication

or “translation” and mediation processes during the dialogue between multiple languages,

values and interests (Luna and Velasco 2021). This aspect is analyzed in the interaction between the heterogeneous actors who

were members of the research group discussed in this work.

Orientation of public policy in science and technology in Mexico and strategic national

programs

The current Mexican government, known as the Fourth Transformation or 4T (2018-2024),

has set out different policy action frameworks that prioritize social welfare and

brings an end to the neoliberal period, seeking a regime shift. The science and technology

area has not been left aside of these changes. In particular, the sector now called

Humanities, Sciences, Technologies and Innovation (HTCI) has evolved toward a paradigm

shift, focusing on the human right to science, the social impact of research, support

for disadvantaged groups through the exchange of knowledge, and participatory research,

seeking universal access to and the democratization of knowledge (Conacyt 2018).

It is worth mentioning that these changes in public policy regarding science, technology

and innovation were embodied with the approval of the General Law of Humanities, Science,

Technology and Innovation on 8 May 2023; on this date, the government agency responsible

for science in Mexico included the H in its acronym, changing from Conacyt to Conahcyt

(DOF 2023).

In this reference framework, the National Strategic Programs’ (Pronaces, in Spanish)

budget program aims to set the basis for the collaboration and convergence of academic

communities to promote a more effective and efficient use of public resources to benefit

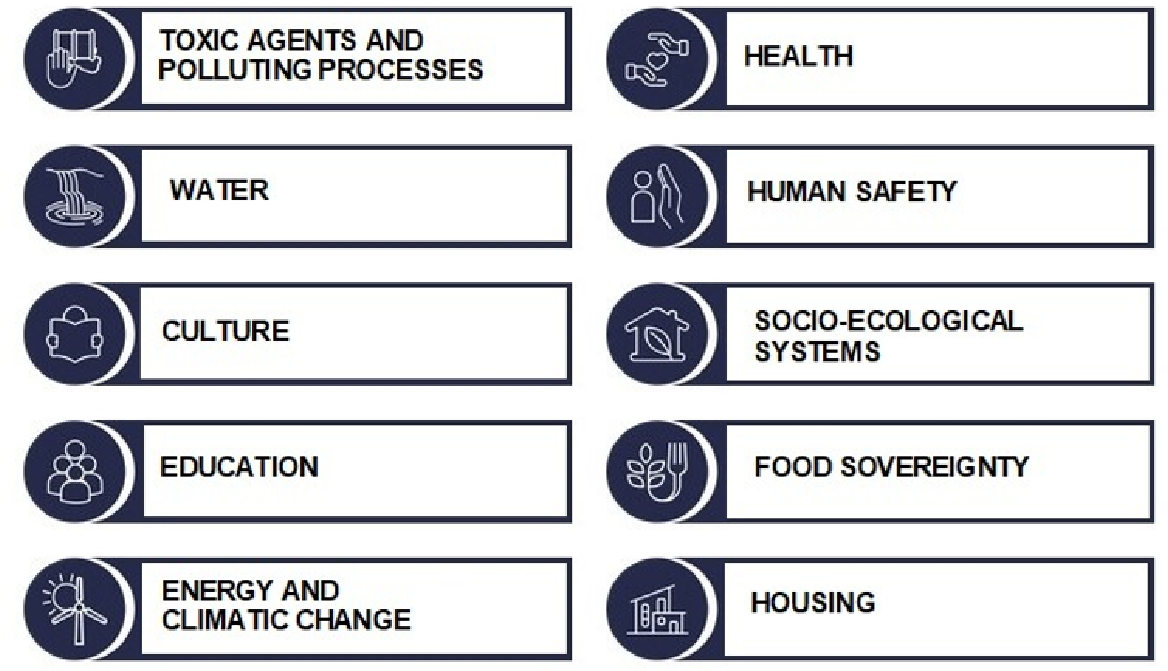

the population and the environment (Conahcyt 2023). This way, Conacyt defined ten Pronaces with a vision of bringing comprehensive

attention to strategic issues, considering theoretical-practical knowledge and seeking

a continuous dialogue to trigger inter and transdisciplinary research and high social

impact (Figure 1). These Pronaces include housing, the framework of the experience analyzed in this

work.

Figure 1:

The ten Conahcyt’s National Strategic Programs.

Source: Conahcyt (2023).

The guidelines established by the government implied submitting a proposal for a pilot

project to be conducted over three months; in case of a favorable response, we would

propose a more ambitious project of broader scope, called the National Research and

Impact Project (Pronai, in Spanish), to be carried out over three years. The pilot

project was given a favorable resolution to receive financing for its execution and

gave way to the formation of the work team, as described in the following section.

However, it did not make it to the next phase, which is suggestive to reflect on the

practical implications of projects of this type, in which a good number of sectors

of the country’s scientific and technological communities have not been involved.

Merida, Yucatan facing the housing problem

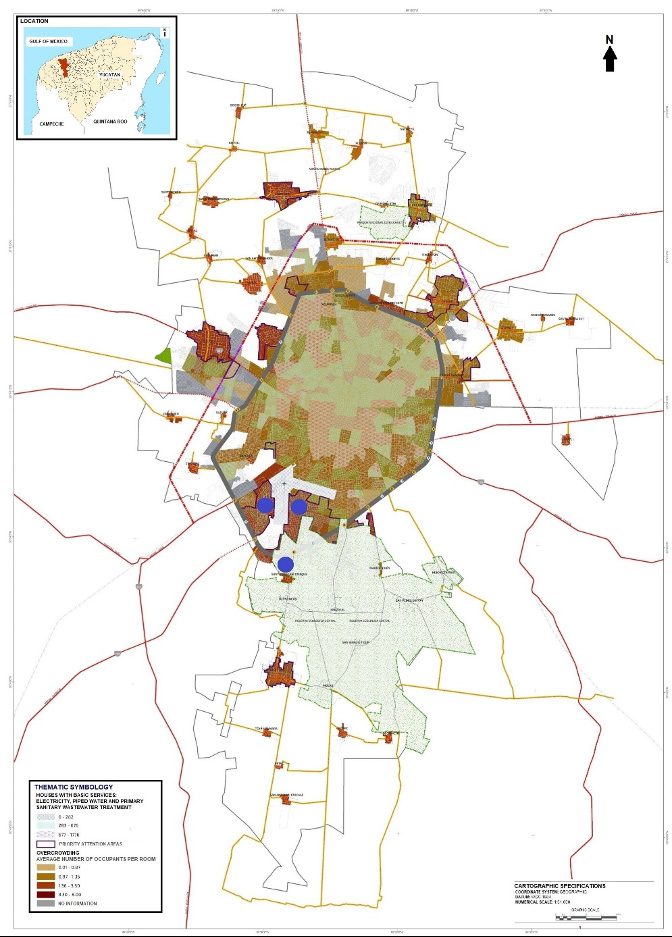

The municipality of Merida, capital of the state of Yucatan, located in the southeast

of the country, has an area of 854.41 km². It is a hybrid territory with an urban

and rural area, which, on one hand, has an urbanized center that starts from the foundational

area towards the outside, with a physical limit represented by the peripheral ring

road; and after this, there is a large extension to the north and south occupied by

47 rural or urban localities (Figure 2). The urban part is made up of neighborhoods and subdivisions, and the rural part

is made up of 12 police stations and 35 sub-commissaries.

Figure 2:

Geographic location of Merida’s priority attention zones.

The purple circles indicate the areas inhabited by the groups of citizens to whom

participatory workshops were given (adapted from cartographic map).

Original source: Instituto Municipal de Planeación de Mérida (2023). Original information in Spanish.

The purple circles indicate the areas inhabited by the groups of citizens to whom

participatory workshops were given (adapted from cartographic map).

Mass housing construction, industrialized and unfocused on the concept of Decent Housing,

became an emerging activity to mitigate the crisis of the henequen industry starting

in the 1980s and became the main source of employment, to the extent that the construction

sector’s share in the state’s GDP surpassed the national average. As a consequence,

the percentage of urban population coming from rural areas increased notably from

that decade onwards, increasing the urban surface and the metropolitan area in the

municipality, where an important role was given to urban and real estate megaprojects

(Iracheta and Bolio 2012, 49-53). On the contrary, in the south, the low value of the land and the low interest of

construction entrepreneurs in acquiring and investing in it (in contrast to the land

in the north, northeast and northwest of the municipality), have led to a less aggressive

change of land use, but still present through some real estate developments.

Merida has been a city in constant dynamism and growth, which has been marked throughout

its history by “a dialectic of inclusion/exclusion that accentuates the social inequality

and spatial segregation inherited from the previous economic model, although with

new characteristics such as the accelerated privatization and fragmentation of the

metropolitan space” (Bolio 2014, 31-32). This phenomenon is explained by the neoliberal reforms imposed since the 1990s,

in particular, the Agrarian Law of the Salinas regime, which allowed the transfer

of large areas of periurban ejido land to private hands.

One of the most important problems faced by the low-income rural population is housing.

This need has been solved by living in small, affordable houses, generally located

in the southern periphery. The low sale or rental prices are one of the main reasons

that make the peripheral areas accessible to the low-income population. However, as

mentioned above, these homes do not have the minimum quality characteristics, so people

live in precarious, overcrowded and unsanitary conditions, as well as in urban insecurity

due to the lack of public services. According to the National Council for the Evaluation

of Social Development Policy (Coneval 2020), in 2018, 79.6% of the population of Yucatan lived in a situation of poverty or

vulnerability due to deprivation and income, which has a direct manifestation in the

lack of access to housing, which this Council considers among the factors of poverty

due to a lack of patrimony.

Opportunities for poor families to access housing are scarce because they currently

have no access to traditional sources of financing, since they do not work in the

formal economy and generally have nothing to back them up in order to be considered

creditworthy with banks. In fact, their only hope of improving the conditions in which

they live is that the government will transfer to them, through social programs, a

minimum resource to improve the quality of their housing; for example, through access

to land and/or construction materials. However, social housing is one of the areas

with the highest rates of backwardness in this region, since the current housing policy,

which withdrew subsidies, has reduced the possibilities of access to housing for thousands

of families in vulnerable conditions (Montañez 2021).

This social problem is compounded by the environmental impact of the aggressive and

vertiginous growth of the city, especially through real estate megaprojects, causing

heat islands in the city, which with climate change are gradually increasing temperatures,

which have been intensifying in the peripheral houses of the city (Villanueva-Solís and Torres 2023). Another worrying situation is the lack of drainage in the Yucatan peninsula, which

means that dirty water drains directly into the subsoil, contributing to the contamination

of the peninsula’s aquifer, the only source of fresh water supply in the region (Febles-Patrón and Hoogesteijn 2008). One more aspect to mention is the high-energy expenditure in homes and establishments,

especially for the use of air conditioners, which leads to an electricity deficit

in the state of Yucatan (Alavez and García 2019).

Due to these problems, the Merida City Council defined the south of the municipality

inside the peripheral ring as a priority attention zone (see figure 6), because it

is where the populations of lower economic resources are settled and where the backwardness

regarding the minimum conditions of habitability and provision of equipment is greater.

In accordance with these guidelines, our research group chose this southern zone,

in order to contribute with the proposal to improve the living conditions of this

sector of the population, with a perspective of environmental sustainability, as will

be detailed below.

The sustainable housing research group: challenges facing the complexity of inter

and transdisciplinary dialogue

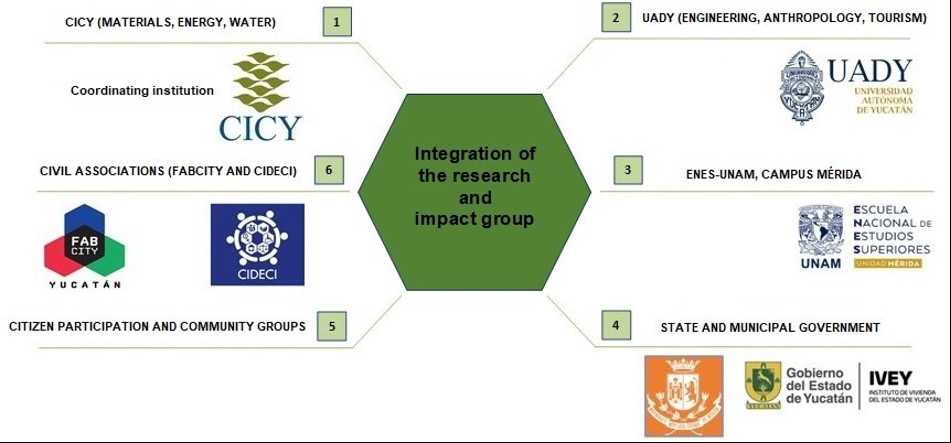

The research-impact group created to address the Housing and Habitat Pronaces brought

together different fields of specialty and academic and life experiences. The initial

academic core had shared a previous project coordinated by the Center for Scientific

Research of Yucatan (CICY inn Spanish) between 2008 and 2012, entitled “Development

of a self-sustainable ecological housing” financed by the Conacyt-Government of the

State of Yucatan Mixed Fund. In the group of this new project specialists from CICY’s

materials area were included, with PhDs in chemical engineering sciences and polymeric

materials, and a master’s degree in communication with experience in science policy

and regional development; from the Autonomous University of Yucatan (UADY in Spanish),

two PhDs participated, one in engineering and the other in architecture; from the

National School of Higher Studies (ENES UNAM Mérida, in Spanish), a researcher in

public policy and a master’s degree in architecture, with experience in social planning,

citizen participation and participatory design of public spaces. From the government

side, officials from the Housing Institute of the State of Yucatan (IVEY, in Spanish),

specialists in urban development and planning, as well as liaison personnel from the

Municipality of Merida for liaison with social organizations and community groups

collaborated. From the civil associations, people with experience in community work

and work in urban areas were involved.

The purpose for each member was to contribute to the project development from interdisciplinary

and transdisciplinary perspectives while seeking to generate a pilot Participatory

Action Research (PAR) that emphasized in the exchange knowledge methodology with the

population involved in the problems addressed. The participants included academic

organizations, municipal and state government agencies, grassroots social organizations

and communities in the study area.

From an institutional perspective, the group was composed by specialists from the

following institutions: Centro de Investigación Científica de Yucatán, A. C. (Center

for Scientific Research of Yucatan; CICY in Spanish, the project applicant and coordinator)

through several research units: Materials, Renewable Energy, Water Sciences and Research

Directorate; Faculty of Engineering and Faculty of Anthropological Sciences, Universidad

Autónoma de Yucatán (Autonomous University of Yucatan, UADY in Spanish); Escuela Nacional

de Estudios Superiores (National School of Higher Studies), Campus Mérida (ENES-UNAM

Mérida, in Spanish); Instituto de Vivienda del Estado de Yucatán (Housing Institute

of the State of Yucatan; IVEY); City of Merida (Directorate of Social Development);

social organizations such as Fab City Yucatán A.C. and CIDECI, A.C.; as well as the

follo- wing Citizen Participation Councils and Community Groups in Merida, Yucatan:

two groups from Colonia Emiliano Zapata Sur 3, a group from Emiliano Zapata Sur 1

and 2; a group from Colonia San Antonio Xluch; and the Community Groups of San Luis

Sur Dzununcán and San Juan Bautista. Figure 3 outlines the integration of the research and impact group.

Figure 3:

PRONAI Research and Advocacy Group.

Source: Cruz et al. (2022). Original information in Spanish.

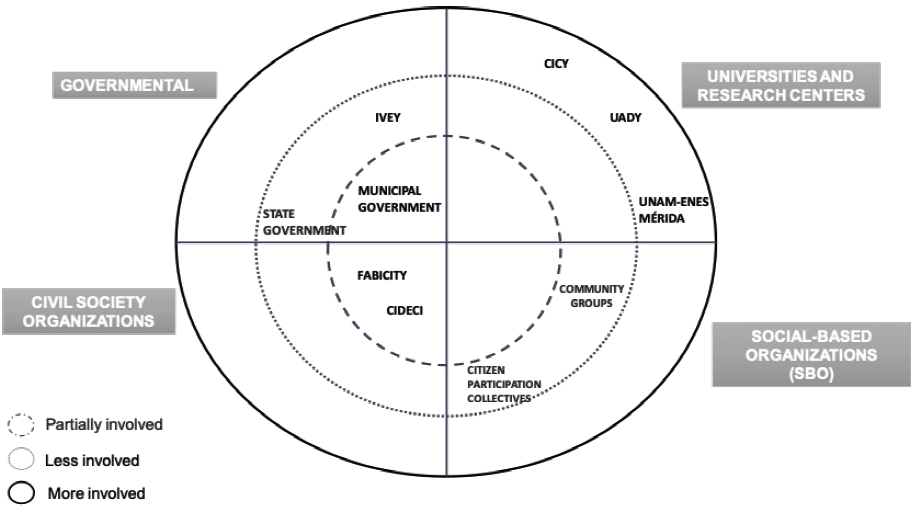

It is important to mention, according to the map of actors (Figure 4), that the degrees of participation and collaboration in the research collective

were different for each sector, which we classified into four groups, namely: 1) governmental,

2) universities and research centers, 3) civil society organizations and 4) social-based

organizations. As can be seen in Figure 4, academic institutions had a higher degree of involvement, secondly, the state government,

through IVEY, as well as social-based organizations and to a lesser extent civil organizations.

This reflects the difficulties of maintaining the commitment and collaboration in

research projects by non-academic actors, since they do not constitute a priority

for them, implying other types of motivations that sometimes is not possible to attend

to in the expected times, given that scientific and technological processes have other

time horizons. Even these transdisciplinary processes achieve better results when

they arise from the initiative of social and productive actors.

Figure 4:

Map of actors. Pronai Advocacy Research Collective.

Source: Cruz et al. (2022). Original information in Spanish.

In this experience, and according to the Conahcyt guidelines, the multidisciplinary

group was integrated to tackle the problems of interest through a comprehensive approach.

The group was made up of 11 members of the advocacy project and 50 participants from

the community groups. However, it is worth mentioning the project development constraints

that emerged from the shift in government policy since neither training nor all the

tools were available to address several aspects required to articulate the project.

This is because this approach transitions from a scheme of basic research proposals

to one of applied research, emphasizing the social “impact”; however, several terminologies

remained undefined from the calls. The following are some controversial aspects at

the time of Pronai project submissions:

-

General research and impact strategy (pilot experiences).

-

Active dissemination strategy.

-

Methods for the inclusion and integration of knowledge and practices by stages.

-

Proposal of internal mechanisms for reflection, recovery, development of practices,

and progressive coordination improvement of all workgroup members.

-

Team performance assessment criteria and indicators.

-

General guidelines for the national propagation strategy (active dissemination).

-

Research-impact group performance.

This undoubtedly reveals a complexity from the postulation of the proposal and the

possibilities of fulfilling these expectations embodied in the scientific policy instruments.

However, the integration of the group itself also presented complexities, such as

the lack of a common understanding of different notions, for example, the concept

of social vulnerability, PPI or industry 4.0 and circular economy. The latter terms,

for example, were suggested by the proposal evaluation group to be included as an

important part of the overall project formulation. Another problematic situation was

the different interests and values of each of the stakeholder groups that interacted

in the project and the implications of this (in relation to time availability, resources,

differentiated objectives and degrees of commitment). The integration of theoretical

and methodological notions was addressed with seminars to establish an integrated

framework around the topics listed above, such as social vulnerability, public policies

and governance. We also worked on topics such as circular economy and industry 4.0,

as well as action research methodologies based on PRA.

Another problematic situation was the different interests and values of each of the

groups of actors that interacted in the project and the implications of this (in relation

to the availability of time, resources, differentiated objectives and degrees of commitment).

Integrating diverse actors, in order to comply with a requirement of the call, such

as social actors or civil association-type groups, implies an enormous challenge of

involvement in the project so that their involvement is not only on paper, but so

that they can really join the dynamics of the working group in an active participation.

This represented a complexity factor to achieve the same level of cooperation among

the different actors. Given that the scientific dynamic has traditionally been to

form work teams between academic peers, opening these spaces to other non-scientific

actors represent important changes in the way work, scope and responsibilities are

shared.

It should be noted that the time allocated for the development of the first phase

of the project (seed project) was only two months. However, the total time from the

formation of the team and the application to this first stage until the PRONAII result

was obtained, was a year and a half, as shown in Figure 5. Establishing an inter and transdisciplinary framework in the time allocated for

this first phase entailed an important effort of openness among the members, to establish

a dialogue between the basic sciences and technologies, and the social sciences. In

addition, the long time between the application of the first phase of the project

(seed project), which took almost a year, generated great uncertainty. Nevertheless,

the integrated collective decided to continue working even without certainty given

the commitment established with the communities and neighborhood groups.

Figure 5:

Timeline in the development of the project.

Source: Own elaboration.

However, the most significant and challenging aspect of transdisciplinary work was

the interaction with the communities of marginal urban zones since many academic researchers

usually work in experimental laboratories following a monodisciplinary approach. Moving

to the social laboratory and applying social methodologies as PAR, implies training

and expertise in other methodologies, as well as a social sensitivity not commonly

experienced in hard disciplines. This involved engaging and bonding with new team

members (academics and fellows) who were better acquainted with these inter and transdisciplinary

work fields. Another constraint was the time available for community group members,

since most were women and mothers who alternated between housework, childcare and

participation in these collective activities.

A final complexity was the excessively long time taken for Conahcyt to provide us

with information on the correct and timely execution of the pilot project. Almost

one year passed between the initial pilot project approval date and the Pronai project

submission, during which, the group had minimal feedback from Conahcyt and, to add

more complications, there were no financial resources provided by the government.

Under these circumstances, keeping a united research group focused on participating

in the project was difficult. However, the project leader and the group members showed

their commitment despite the lack of funding certainty. During those months, internal

seminars were held and progress was made in the participatory analysis of the housing

conditions by interacting with community groups. All this led to greater integration

of the research group and to acquiring new learnings as a team.

Experience from the interaction between academic and community groups

Within the Participatory Action Research (PAR) methodological framework applied in

the project, participatory workshops took place with community groups in southern

Merida, where these groups live in priority attention areas as defined by the Instituto Municipal de Planeación de Mérida (2023) (Municipal Planning Institute of Merida) and as we indicated above, where housing

is most precarious, including overcrowding and limited access to basic services. The

location of the areas to carry out the pilot experiences was made based on the review

and analysis of the information contained in plans of the city of Merida such as the

one in Figure 2, showing the priority attention zones defined by the Municipal Planning Institute

(Implan). These areas are those surrounding the city’s airport (the areas of Los Robles,

San Marcos Nocoh, San Antonio Xluch I, II and III, and the neighborhoods of Dzununcan).

It was decided to also work in areas located outside the peripheral ring (Figure 2), given that they also present a significant number of actions requested to address/support

housing needs, information that was provided by IVEY.

Workshops were delivered following the IAP methodology mentioned above. The aim was

to motivate householders to get involved and contribute, sharing to proposed solutions,

the issues related to their houses from their own needs, wishes and experiences with

the support of specialists from various fields.

The first contact with the selected communities consisted of an introductory workshop

held with representatives of citizen councils in the study areas, supported by the

Department of Citizen Participation of the Directorate of Social Development, Municipality

of Merida, who allowed us to use their facilities in Integral Development Centers

located near the selected communities during the workshops (Figure 3). To this end, its promoters assisted us in inviting the leaders of each neighborhood

and other interested people to participate. Citizen Councils are composed of neighborhood

citizens who meet regularly (weekly or monthly) to discuss community issues and manage

improvements with the authorities. Promoters act as liaisons between Citizen Councils

and the City of Merida.

Subsequently, participatory workshops were held to gather data on the urban environment

and housing needs. Table 1 summarizes the activities carried out in each workshop. The aim was that the results

of these workshops would contribute, both to the design of sustainable housing as

well as to the decision making process regarding the training of these communities

for the possible self-production of housing in case the Pronai project was approved,

focusing on their areas of opportunity, on an analysis of their activities and the

real characteristics of the houses. As of the writing of this document, this phase

has not started, as the full proposal was not considered by Conahcyt and is dependent

on external funding sources for its continuation.

Table 1:

Summary of the participatory workshops delivered.

|

Workshop

|

Date and place

|

Addressed to

|

Description

|

Target

|

|

1. Workshop for approaching and presenting the work project to representatives of

citizens’ councils.

|

-

Emiliano Zapata Sur, February 17, 2022.

-

Crescencio Rejón, March 16, 2022.

|

Members of Citizen Councils of the southern zone of the city of Merida.

|

-

1. Application of a survey regarding their homes.

-

2. Presentation of the Project and the work team.

-

3. Recommendations of the councils, for the application of the following workshops.

|

Workshop, presentation to the community and planning of future workshops.

|

|

2. Participatory workshop to diagnose the urban environment

|

Emiliano Zapata Sur, May 9, 2022.

|

Members of Citizen Councils in the southern area of the city of Merida.

|

-

1. Application of a survey regarding their homes.

-

2. Mapping of transportation routes and opportunity zones in your community. Analysis

of existing infrastructure and equipment.

-

3. Writing about the historical line of your community and housing.

-

4. Drawing by children about their housing and environment.

|

Gather updated information from the perspective of the residents regarding the urban

environment and the background of their community.

|

|

3. Participatory workshop to diagnose housing needs

|

CDI Emiliano Zapata Sur, May 13, 2022.

|

Members of Citizen Councils of the southern zone of the city of Merida.

|

-

1. Drawing up a floor plan of your home and analyzing your activities.

-

2. Analysis of strengths and weaknesses of your home.

-

3. Description of your desired home.

|

Collect information regarding their housing needs, for subsequent design and implementation

of training and participatory workshops on selfconstruction.

|

Between the three workshops held, about 67 people participated and, particularly in

the third workshop, there was an important presence of children. During the participatory

workshops, surveys were applied to citizen representatives about the characteristics

of their homes and various activities were implemented, based on participatory methodologies

for habitat design, such as the mapping of community needs, the history of the community,

“judging your home” or “drawing my ideal home”, which, adapted to the case, were based

on the Living- stone methodology for participatory housing design (UN Habitat 1996).

It is worth mentioning that 99% of the representatives who attended the workshops

were women, between 30 and 60 years of age, and more than 70% were housewives and

mothers, who expressed their gender perspective in their list of needs. At their request,

a space was created for children, who, through drawing activities, also considered

their vision of the place where they live. A very relevant aspect that stands out

in the observations of the workshops is that they are very well organized and perceive

their neighborhoods or their blocks as safe, but not the place across the street.

There is an expression of belonging and self-care.

The set of experiences, in which methodologies with diverse characteristics were applied

and developed, made it possible to generate an improved version of the advocacy model,

which, in principle, can be adapted in a differentiated manner to the particular conditions

of different communities in which social problems associated with habitat and housing,

particularly overcrowding, are present.

It was noted as an important aspect, to give continuity to the activities that include

the training of the community about productive processes of materials and housing

construction processes, as well as to follow up on the workshops and evaluate the

results in greater depth. The type of activities to be carried out will depend on

the results of the analysis of the workshops conducted in this project, regarding

the social reality of the selected community. A series of coordinated actions should

be implemented to further involve the different sectors involved in the housing and

habitat problem through public dissemination and communication activities that promote

the positioning of the topic, which will facilitate the processes of social appropriation

to contribute to universal access to knowledge.

The dynamics with the communities showed their full willingness to participate, which

shows a potential to be explored in future projects of this nature. It is worth mentioning

that, as a result of this initiative and not obtaining Pronai funding, CICY promoted

its own project to continue the advocacy work with social groups called “Elaboration

of a diagnosis to increase the habitability and durability of housing for the vulnerable

population of Merida, Yucatan” (Rivas et al. 2023), in order to encourage more participation of the target population in the development

of designs that would take advantage of the large spaces that usually have the houses,

to use them for more vegetation, as well as for their learning in the elaboration

of fibro-reinforced concrete and evaluation of different alternative materials in

their housing. The approach with the neighborhood groups, in short, made it possible

to initiate this process of exchange among the social group in order to establish

a dialogue of knowledge and initiate the actions of social retribution of knowledge

that will make it possible to build true transdisciplinary work in the future.

Conclusions

The transition from monodiscipline to inter and transdiscipline, coupled with the

construction of common analytical frameworks, has become a central challenge for academic

research to advance in solving complex social and environmental problems. To this

end, it is necessary to be open to other frameworks and approaches to reality, as

well as to interact with other types of relevant and, at the same time, socially robust

knowledge. On the one hand, interactions shall promote dialogue between different

areas of knowledge, both academic and nonacademic; on the other, it shall encourage

the articulation of knowledge with society to face the current socio-environmental

crisis.

An important factor, undoubtedly, was the effort to integrate the project in its entirety.

However, the fact that it was not approved by the funding agency meant that the collective

and the communities invested some time in an unfinished process, approximately two

years of work from the beginning of the process. This could lead to the creation of

false expectations due to the gap between academic times and the times of other social

actors, although it also led to the construction of lessons learned in the advocacy

collective.

The difficulty of assuming the challenges that this project implied for a research

center that by its nature only has researchers in the area of basic and natural sciences,

can be seen as a difficulty, but also as an opportunity to open up to participate

with other institutions with training in social sciences, and even the possibility

of integrating students from different degrees and participate through experience

in the formation of human resources.

The transformation in the current Mexican government regarding scientific and technological

policy has led to significant challenges in academic communities since it forces a

reconfiguration in the roles and characteristics of research groups, as well as in

the methodologies adopted and the objectives pursued, which are to be reoriented towards

social impact. Although this is a beneficial scope, it should not be the only framework

promoted to generate new knowledge. Moreover, in practice, it involves major challenges

in the organization of science that cannot be established overnight; instead, it is

a mid to long-term process that requires a formative evolution to achieve greater

openness to dialogue between specialists from different disciplines and with bearers

of non-scientific knowledge; the latter implies that researchers and scientific institutions

should generate new strategies for linking with social groups. These new scientific

forms and dynamics therefore imply a gradual learning process, but in this case it

was carried out under urgent conditions to meet the requirements set by the federal

government.

The experience discussed in this paper highlighted the need to improve methodologies

to interact with communities facing social and environmental issues associated with

habitat and housing, particularly under overcrowded and social marginalization conditions.

One of the lessons learned is that replicating these processes in other experiences

is unfeasible if they are not first customized to the particular conditions of each

community so that they are effective in the joint production of knowledge and, above

all, in the implementation of solutions to problems identified collectively. Considering

the cultural context and the timing, needs and degrees of commitment in these initiatives

led by academic communities is essential to place the gender perspective and children,

key actors in the participatory processes, at the center of the interactions.

On the scientific sector, working with community groups and governmental and civil

actors also imply greater effort and commitment. In particular, the Sustainable Housing

research group should continue carrying out activities such as training the community

about material production and housing construction processes, as well as follow-up

and evaluation of results. Finally, improving the planning and execution of coordinated

work strategies is essential to further engage the different sectors involved in housing

and habitat issues. ID