Introduction

Mexico is one of the few countries that combine enormous fishing and agricultural

legacies. It is one of the top 20 nations worldwide in terms of coastline (11,600

km), inland waters (2,500,000 ha), exclusive economic zone (3,000,000 km2) and fishing activity. Its fishing sector incorporates 69,000 small-scale fishers

and 8,000 offshore or large-scale fleet fishers (88% men and 12% women). Small-scale

fisheries commercially capture approximately 665 species, while the offshore fishery

is dedicated to the capture of 48 species (Conapesca 2018). It is estimated that approximately one million families in Mexico are formally

or informally employed in pre and post-capture processes, with an increased participation

of women during the initial and final stages of the commercial cycle (Ibid ). Furthermore, Mexico is also one of the eight great centers of origin, domestication

and diversification of plants (Harlan 1971). Close to 200 species of edible crops of great global food importance have their

epicenter in Mexico (Casas et al. 2007). Currently, Mexican small-scale farmers are grouped into around 32,000 agrarian

communities distributed in all the states of the country and covering around 90% of

the municipalities nationwide, forming a sector of approximately six million families

(Morett-Sánchez and Cosío-Ruiz 2017). Of the entire Mexican small-scale agriculture sector, 80% is represented by rural

subsistence units with market linkages (FAO 2020). Despite this valuable fishing and agricultural legacy, Mexico is currently subsumed

in a deep food and malnutrition crisis. According to the National Council for the

Evaluation of Social Development Policy (Coneval, by its Spanish acronym), 55% of

Mexican households present some manifestation of food insecurity, while 24% of the

national population live under conditions of food poverty and 12% of the rural areas

experience chronic malnutrition, including one million children (Coneval 2022). Of the national population living in food poverty, 70% are indigenous people, while

one in four children with chronic malnutrition are indigenous (Ensanut 2018).

In order to analyze the paradoxical and complex food reality of Mexico, our study

centers on the food regime approach. Coined by Friedmann and McMichael (1989), this approach allows us to analyze, from the theoretical bases of the political

economy, the modern world-system and center-periphery, the dynamics and structuring

of the rules and devices that govern the production, distribution and consumption

of food on a global scale. Such rules and devices have been adjusted historically,

and it is therefore possible to recognize different stages within the global food

regime: the colonial, agro-industrial, supermarket revolution, and an ultimate stage

of financial speculation and ‘green’ or ‘blue’ dispossessions (McMichael 2009).

In Mexico, people are subordinated to (neo)colonial trade logics in which we export

quality food while importing second-rate products. For instance, we export finfish,

mollusks and crustaceans to countries with high commercial standards such as the United

States, Japan and Spain, and import fish fillets, among others, of frozen ‘basa’ from China and Vietnam (Conapesca 2018). Despite ranging around the top 15 countries worldwide in fish catch, Mexico’s annual

per capita consumption of fish and seafood ranges around 13 kg, a value well below counterpart

countries in terms of fisheries such as Japan, China, Norway, Portugal and Spain with

values of 40 to 65 kg (Ensanut 2018).

Mexico also imports agricultural products comprising more than half of that consumed

nationally, including maize and beans, the basis of the people’s diet, in exchange

for elite exports such as avocado (Appendini 2014). Moreover, the agro-industrial regime has led to high dependence on chemical inputs

in order to produce food. In this regard, around 80% of small agricultural production

units in Mexico use at least one technology of the “Green Revolution” (Altieri et al. 2021). Another negative impact on small-scale producers has been the irruption of large

national and transnational supermarket chains because, given their capacity for commercial

monopolization of production, urban, peri-urban and rural consumers have turned to

these spaces to satisfy a large part of their food requirements, not only for ultra-processed

products, but also for fish, seafood and foods of agricultural origin (Schwentesius and Gómez 2008). Finally, to understand the small-scale producers’ exclusion process, the national

susceptibility to food speculation and the increase in corporate agricultural frontiers

due to the lack of price stabilization and regulation mechanisms must be considered,

as well as the neglected regulation of agrarian and coastal dispossessions (Robles-Berlanga 2012).

The historical turning point from which the dynamics described began to be exacerbated

was the neoliberal dawn of the 1970s and the implementation of the North American

Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1994. Since then, Mexico has experienced what several

authors have described as the disarticulation of national fisheries and agriculture

(Calva 2019, 615), and the consequent development of food dependence (Barkin 1987). In the initial stages of neoliberalism in Mexico, fishing cooperatives (Cisneros-Mata et al. 2023) and farming organizations were dismantled, as well as effective state participation

in popular food supply (Yúñez-Naude 2003). Thus, for small-scale fishing and farmer families, as well as for marginalized

urban and peri-urban households, since NAFTA began (Gálvez 2018), there has been a strong tendency towards food insecurity and the double nutritional

burden syndrome: the coexistence of overweightness and malnutrition (Varela-Silva et al. 2012). In farming households, protein deficits have been documented; in fishing households,

there are dyslipidemia risks due to lack of eating habits that involve fruits, vegetables

and cereals. This can be added to the fact that the diets of both groups share with

those of poor urban and peri-urban households a high consumption of ultra-processed

foods typical of the widespread ‘westernization’ of the Mexican diet (Popkin 1999).

Despite progressive discourse in the national public realm, following the recent transition

of power from ‘pro-neoliberal’ to a ‘leftist’ government, policies for reducing public

spending and the dynamics of dismantling the fishing and agricultural means of production

have continued. As antagonistic as it may seem, the neoliberal paradox of post-neoliberal

governments can be understood from the reasoning of neoliberalism as a structuring

process and not only as a political ideology. Therefore, beyond changes in political

representativeness, the factual powers continue to reproduce themselves (Fletcher 2019): “neoliberalism, so long, we hardly knew you” (Keil 2009, 231). The fisheries sector has been one of the most affected by the leftist government:

22 of the 23 federal fisheries support programs have disappeared under the current

administration (Cisneros-Mata et al. 2023). It is noteworthy that the budget for inspection and surveillance activities has

almost disappeared, even though approximately 60% of the fish catch in Mexico is extracted

without fishing permits, using irregular fishing gear, during closed fishing seasons

or even illegally within marine protected areas. On the other hand, greater public

efforts have been channeled into the agricultural sector led by the Ministry of Agriculture

and Rural Development (SADER, by its Spanish acronym) where two antagonistic forces

dispute its focus between the agroindustry and peasant-agroecology (Bazán Landeros and Torres-Mazuera 2021).

Regarding small-scale producers’ leadership, over the last four decades, a large majority

of the fishing and farming organizations in Mexico have concentrated their power in

old leaderships and have attended more to programs of political opportunism than to

movements of social struggle (Carton de Grammont 2008). For instance, Mexican fishing and farmer organizations present very limited participation

in international social movements of great importance in other Latin American contexts,

such as the World Forum of Fisher Peoples and La Via Campesina.

Given this complex national panorama, in this paper we pose the following research

question: how, in the face of the exclusion processes of the current food regime,

abandonment of public policies and erosion of most of the sectoral organizational

capacities in Mexico, can small-scale fishers and farmers, and urban and rural consumers

be articulated in order to improve their productive, commercial, food and nutrition

problems within their living contexts? Thus, the aim of the study is to outline a

theoretical-methodological proposal, based on our experience and that of colleagues

with decades of research in fishing and farming territories, in order to provide the

scaffolding for the transdisciplinary articulation of complementary and alternative

territorial circuits of production-distribution-consumption that connect coastal areas,

the rural inland and small-medium cities on a micro or meso-regional scale, from which

food systems can be relocated without compromising the fishing and agricultural resource

base. In such articulation, collaboration between fishing and farmers’ families and

organizations themselves, as well as NGOs, academics and government are of utmost

importance, which has a high potential to occur given the previous collaborative networks

that already exist in many Mexican territories (e.g., Herrera and Guerrero-Jiménez 2020; Bello-Baltazar et al. 2020). It will also be of utmost relevance to find mechanisms for the participation of

a whole critical mass of reflexive consumers, capable of demanding fairer forms of

food commercialization, such as nested markets (Van der Ploeg et al. 2022).

The article is structured in six sections. After this introduction, the second part

describes the transdisciplinary methodological approach, and the third part introduces

the Yucatan Peninsula (YP) as a case study, describing the problems currently faced

by its small-scale fishers and farmers. The fourth part analyzes the type of results

that could be obtained of the proposed approach, while fifth section focuses on discussing

challenges and limitations of the proposal. The final part contains concluding remarks

considering the scope of this proposal in terms of its application to other related

contexts in Mexico and in Latin America.

The transdisciplinary approach

The whole research approach comprises a combination of theoretical concepts and analytical

frameworks, which have been developed over several decades, primarily by scholars

from Mexico and other regions of Latin America, although we also incorporate some

reflections of international scope, such as the study of food regimes and transdisciplinary

discussions. In particular, the development of the study benefited from our participation

in the following five specific academic-social-political interface experiences: 1)

the organization of the international seminar “Dialogues for the construction of agri-food

sovereignty and security in Mexico” held in 2020, in which a group of 60 academics,

government officials and leaders of national and international organizations debated

the productive and food paths of the country (https://www.iis.unam.mx/soberania-agroalimentaria/); 2) publication of the book Socio-environmental regimes and local visions: transdisciplinary experiences in Latin

America, which provides a transdisciplinary framework to address different socio-environmental

regimes using case studies from seven Latin American countries (Arce-Ibarra et al. 2020); 3) our collaborative work in multidisciplinary groups or research and influence

teams (RIT) involving the development of two project proposals, namely “Artisanal

fishing and food sovereignty: innovation niches to promote consumption and expand

the distribution of fishery products in the Yucatan Peninsula” and “Popular and solidary

agri-food trade corridor between milpera and Puuc regions in Yucatan” funded by the Mexican National Council of Science and Technology

(Conacyt, most recently Conahcyt, by its Spanish acronym), to address national issues

using an integrated approach to innovation and influence; 4) our experience participating

in platforms, networks and social movements related to fisheries and agriculture,

including the Community Conservation Research Network (CCRN, https://www.communityconservation.net/), the Too Big To Ignore: Global Partnership for Small-Scale Fisheries Research (http://toobigtoignore.net/), and the technical team of La Via Campesina North America; and finally, 5) our collaborative field work, conducted over a period

of almost three decades, with fishing and farming communities of the YP, which leads

us to empirically illustrate the proposed approach for this specific regional context.

Leveling the common theoretical ground

Our methodology is based on what we have called the transdisciplinary approach to

research and influence (TARI). In Mexico, from 2019 to date, Conacyt (Conahcyt) has

promoted influence or social transformation as part of research projects that seek

to solve the country’s most pressing problems, including the quest for and promotion

of national food sovereignty. In particular, the idea of ‘influence’ implies promoting

the improvements, change or social transformation required to partially or totally

solve the addressed research problems (García-Barrios 2019).

Thus, a TARI begins with the formation of a multidisciplinary working group called

the research and influence team (RIT), which is responsible for the entire process

of the research project. Based on interpellation with the subjects and social realities

of the study area, the RIT seeks to move the research process towards a transdisciplinary

realm. The RIT is generally composed of experts with different specialties. By working

and interacting within a RIT, participants should recognize that they work “in dialogue

with the different” (Merçon et al. 2021, 199). Some operational ground rules of collaboration are that, in general, the RIT does

not work in a top-down manner guided by any leader, but rather the participants work

horizontally, with leadership that is most often rotated, promoting empathy and an

openness to be able to teach, and learn from, any of the people involved in the RIT

(see Chuenpagdee and Jentoft 2019; Bello-Baltazar et al. 2020). The main tasks of the RIT are: i) selection of a theoretical-conceptual framework

for the research; ii) analysis and discussion of the philosophical bases of the type

of transdisciplinarity that the study will employ; iii) identification of the research

and influence problem to be addressed, as well as selection of the study area; and,

iv) carrying out the required fieldwork, analysis of the results, and socialization

of the insights resulting from the research with the communities of the study area.

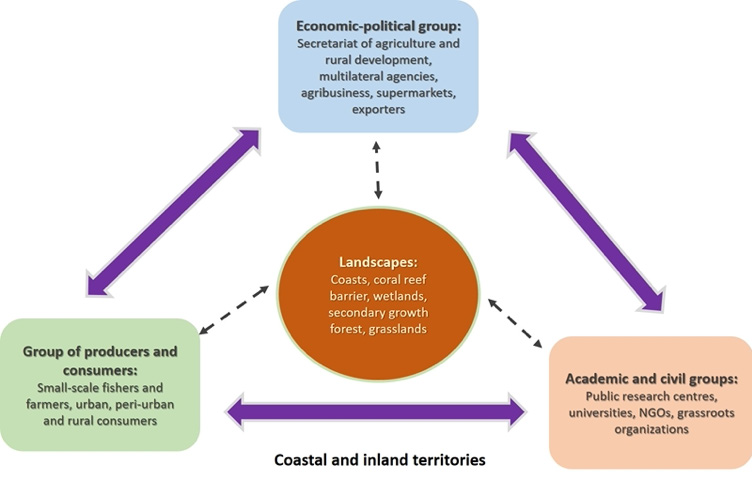

Regarding the conceptual framework for the research (although each RIT would choose

one that suits its conditions), here we propose the model of local socio-environmental

systems (LSES) as a basis for reflection (Parra-Vázquez et al. 2020) (Figure 1). The LSES portrayed in Figure 1 is a production system in which it is explicitly recognized that its functioning

has been conditioned for several decades by the rules imposed by the global multilevel

food regime. Under this premise, the possibility of small-scale producers maneuvering

to make major changes within the system is limited (Parra-Vázquez et al. 2020). A LSES refers to a complex small-scale production system, located in coastal-marine

(fishing) and/or terrestrial (agricultural) territories. Each production system uses

the landscape units contained in its territory as resource base or as inputs. Three

main human groups interact in each LSES: a) group of producers and consumers; b) the

socio-academic group, which can include people with various profiles, for example,

professionals, researchers and representatives of NGOs; and, c) the economic-political

group comprising government officials from the three levels of administration, as

well as middlemen and entrepreneurs (Figure 1).

Figure 1

The local socio-environmental system (LSES) model as a basis for reflection of our

methodological approach.

Source: Adapted from Parra-Vázquez et al. (2020).

With respect to the transdisciplinary philosophical bases that the research will use,

there are different positions and schools of thought offered by the literature, from

Piaget (1972) to the most recent reflections published for the Mexican and Latin American contexts

(Merçon et al. 2021). Since we recognize that each RIT must organize its own exercise for each territorial

context where any study is carried out, the following paragraphs only present some

reflections, which are basically related to our own conception of one, among other

possible transdisciplinary approaches.

Literature review reveals that there are different definitions of the words transdisciplinary

and transdisciplinarity. In reviewing their etymological origin, Basarab Nicolescu

reports that the prefix “trans” “is a Latin word meaning at the same time, in between,

across, and beyond.” (Volckmann 2007, 78). In other words, “Transdisciplinarity is completely different [to interdisciplinarity]

in the sense that it puts the problem of the information that circulates in between

disciplines, across disciplines, and even beyond any discipline” (Volckmann 2007, 77). Furthermore, Nicolescu postulates that transdisciplinarity is a context in which

it is recognized that there are “different levels of reality” (Volckmann 2007, 80) in different domains of the world.

Nicolescu’s proposal of different levels of reality also applies to domains of human

society. In this regard, we extend this idea to the formation and development of the

RIT: “There are levels in ourselves, in our own understanding, representation, languages

and so on, and even levels of reality of the Subject” (Volckmann 2007, 80). If this complexity of reality is recognized, then the contributions of each member

of the RIT require consideration and discussion that, most probably, ‘the different

ones’ in dialogue -including the communities in which the study is developed- will

collaborate from different levels of reality, as well as from different worldviews.

Other complementary views on transdisciplinarity indicate that it is the amalgamation

of scientific knowledge with social practices (Lang et al. 2012), which is context-specific and where power relations and interculturality generally

emerge (Zamora 2020; Bello-Baltazar et al. 2020). Several authors recognize transdisciplinarity as a relatively new concept (Choi and Pak 2006; Volckman 2007) one that can be conceived as a tool, but also as an intrinsically unfinished project

permanently under construction (Max-Neef 2005).

A practical component of transdisciplinary approaches

From our own experience, one of the practical components of a transdisciplinary approach

involves ‘how to integrate’ the parts of a whole (i.e., the story of the project,

from start to finish), and relates to moving from the multidisciplinary or additive

aspect of the research process, first to an interdisciplinary realm, and then to transdisciplinarity

(Arce-Ibarra et al. 2020). We have conducted this exercise by selecting and discussing key categories that

serve as the explicit axes, or ‘bridging’ concepts, used as threads that run transversally

through the research process (see Arce-Ibarra and Gastelú-Martínez 2007; Puc-Alcocer et al. 2019). To examine the exclusion processes of the global food regime, we have chosen the

concepts of ‘food regime’ (from political economy), ‘territorial production-consumption

circuit’ (from economic anthropology) and ‘territorial innovation niche’ (from ecology,

transitions literature, and political sociology), as the key interrelated concepts.

From these concepts, with the participation of the RIT and the beneficiary social

subjects of the study area, knowledge and influence can be created while weaving the

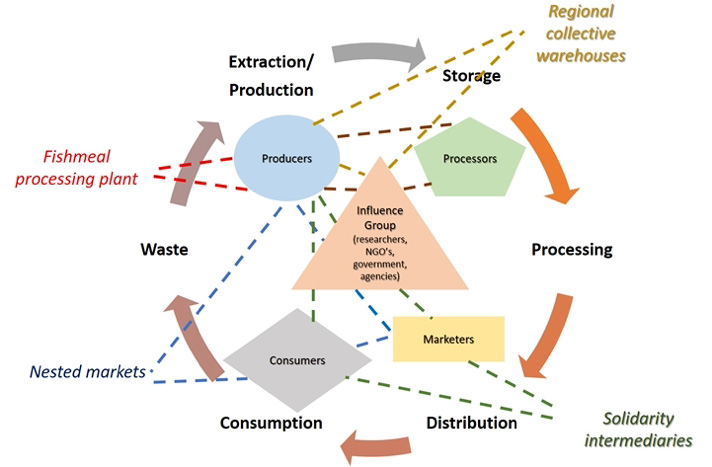

story of the study. We refer to a territorial production-consumption crcuit (TPCC),

also known in the literature as a value chain (Coronado et al. 2020), as the productive process in which the participating social subjects and their

interactions are analyzed, from obtaining the raw materials to consumption, through

processing, distribution and commercialization. A TPCC can be mapped, and its types

of interactions identified and analyzed, including the power relationships (Coronado et al. 2020). When it is considered necessary to make changes or modify a TPCC (for example,

to create more sales or consumption access points for certain users), it is necessary

for the social actors involved to analyze the process and identify innovation niches

to carry out the proposed modifications. According to Ingram (2015), an innovation niche is composed of sources of ideas and areas of opportunity that

generally become new practices and actions, which, being outside the status quo, represent a challenge to that which is already established, in this case, the global

food regime.

Regarding the epistemological bases for creating knowledge, and considering Nicolescu’s

levels of reality, we argue that it will most likely be impossible for the RIT to

subscribe to a single paradigm of knowledge. Instead, we propose using epistemological

pluralism (Miller et al. 2009) with elements of critical interculturality, since all the voices of the social subjects

in the area of influence must be included (McDonell 2000; Zamora 2020). We refer to epistemological pluralism, because there will be a common arena (e.g.,

those spaces of collaborative work) in which the encounter and incommensurability

of various ways of creating knowledge, from orthodox to emerging paradigms or sociologies

(e.g., De Sousa Santos 2009), will be allowed. This provides an opportunity to be inclusive and to consider the

diversity of ways of working of the different RIT members. However, for each way of

creating knowledge, each member (or subgroup) of the RIT will present seminars at

the working meetings, where they will show the benefits and criticisms of the particular

epistemological paradigm to which they subscribe. In addition, they must show: a)

how their paradigm considers (or excludes) the voices and worldviews of marginalized

groups -such as small-scale fishers, farmers and popular consumers; b) how they would

combine their results with the social and cultural practices of the territorial circuits

under study; and, c), how the paradigm they use contributes to the social transformation

required in the research and influence project (sensuGarcía-Barrios 2019).

Research methods

To carry out this type of study, we propose a combination of qualitative and quantitative

research methods, all forming part of the participatory action research (Park 1992). Qualitative methods refer to the use of ethnographic techniques, participant observation,

community meetings and workshops, focus groups, life stories, social network analysis,

social mapping, and the elaboration of photographic or video documentary memories

-all with the informed consent of the social subjects (Bernard 1995). Quantitative methods comprise parametric and nonparametric techniques (Ramsey and Schafer 2002). Likewise, we propose to consider a third conglomerate of heterodox methodological

and epistemic tools typical of complexity sciences (Rivera-Núñez et al. 2021) that seek to move from analysis to synthesis and to the integration and multi-actor

discussion of results. The methodological approaches include the companion modeling,

agent-based computational simulations and serious socio-ecological board games (García-Barrios et al. 2016; De La Cruz et al. 2023).

Lastly, as part of the participatory action research cycle, it is essential to systematize

research processes and influencing experiences (Jara Holliday 2012), as well as to generate explicit spaces for social learning (Reed et al. 2010). Social learning refers to a higher order of discernment in which the RIT can challenge

(or entrench) previous values, norms and beliefs in order to collectively deepen the

constraints and opportunities that presuppose the quests for transformation or territorial

niches of innovation within given socio-environmental regimes (Fazey 2010).

The Yucatan Peninsula as a case study

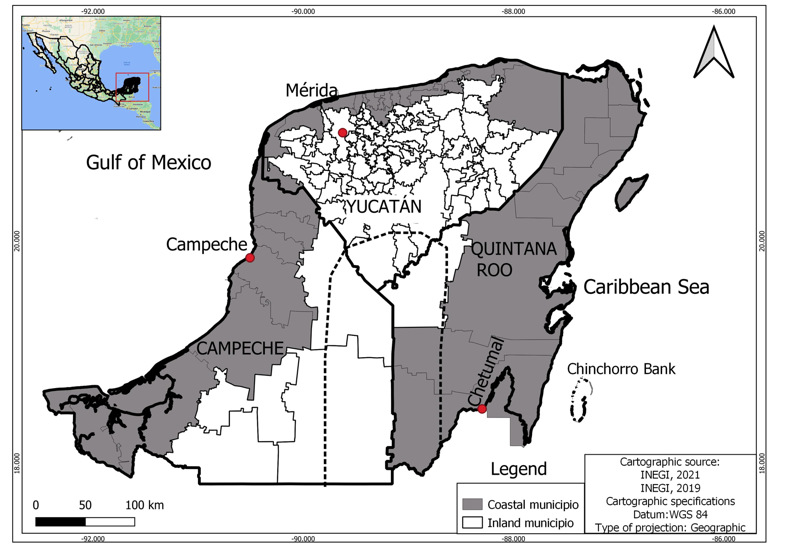

We selected the Yucatan Peninsula (YP) in order to illustrate the proposed transdisciplinary

approach. This region, comprising the three states of Campeche, Yucatan and Quintana

Roo, is in southeastern Mexico and has an area of 181,000 km² and a population of

almost 5 million inhabitants (Jouault et al. 2022). The YP is part of the ancestral territory of the Mayan people who settled in this

area at least 5000 years ago (Rivera-Núñez et al. 2020). In the 21st century, the Mayan culture is expressed in the YP, among other things, through the

use of Yucatec Mayan language, which is spoken by nearly one million people in nearly

one thousand rural and coastal communities in this area (Bello and Estrada Lugo 2011). The culture is also expressed through the practice of slash-and-burnt shifting

agriculture called milpa. It is estimated that approximately 50% of the population of the YP lives in coastal

communities (Coronado et al. 2020) and about 80% of the population occupying inland territories live less than 200

km from the coast (see Figure 2). However, except for periods of food constraint, such as those caused by the sanitary

contingencies of recent years, there is little exchange and trade between the fishing

and farming communities (Figure 3). The presence of these people and their traditions in the area implies that, when

this study is conducted therein, the RIT will encounter social actors with culturally

diverse local knowledge -from either the environmental, fishing or agriculturist realms.

It is with these people and their worldviews that the RIT is expecting to devise problem-solving

strategies related to their fishing and agricultural production and commercial systems.

Figure 2

Area of study for the transdisciplinary research approach. Coastal municipalities

are shaded and a zone of influence extending to 200 km in distance from the coast

is delimited in dotted lines.

Source: Produced by M. C. Saida Ochoa Huchin.

Figure 3

Solidarity exchanges of fish for fruits and vegetables among small-scale producers

of the coastal municipality of Dzilam de Bravo and the inland municipalities of Dzilam

González and Dzidzantún, Yucatan, during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020.

Source: Alianza Peninsular para el Turismo Comunitario.

The research and influence problem

In general terms, despite the importance of primary sector activity in the YP, only

52% of the total population in Campeche, 60.3% in Yucatan and 65.1% in Quintana Roo

had achieved food security by 2018 (Coneval 2022). These values may vary depending on socio-environmental (e.g., presence of prolonged

droughts or hurricanes), socio-economic (high rates of migration of young people from

rural areas to urban and touristic areas) and political (presence of programs that

encourage production) factors.

In the last decade, YP’s fisheries operated with 675 semi-industrial fleet vessels

and 10,916 artisanal fleet boats. Considering both fleets, close to 27,000 individual

fishers were employed (Conapesca 2018; Coronado 2020). YP’s smallscale fishing systems are in coastal-marine areas where, depending on

the time of the year, closed seasons and the depth at which they are fished, fish,

elasmobranchs and invertebrates can be caught using a variety of fishing gear (such

as hand lines, fishing lines, gill nets, free or apnea diving, ‘hooka’ or compressor diving, and ‘jimba’, among others). Once the fishery product is caught, it is landed at the docks of

each community to continue through the network that makes up the territorial circuit

of distribution, marketing and consumption of fish and seafood (TPCC). Species of

higher economic value (such as octopus, lobster, or some fish such as grouper and

hogfish) are marketed either to the local tourist market or delivered to processing

plants, while medium and low value species are sold in the same locality and form

part of the domestic consumption in the households of the fishers themselves.

Despite the size and contribution of the sector to local, national and international

food systems, the literature reports (and the fishers themselves recognize) that the

coastal fishing sector faces several problems, including the fact that several species

are overexploited, and their catches are declining (Table 1) (Arreguín-Sánchez and Arcos-Huitrón 2011; Bravo-Zavala et al. 2022). Another striking problem is the difficulty of marketing medium and low economic

value products in regional and national markets (J.C.C.N. fisher from Telchac Puerto,

personal communication, October 2021).

Table 1

Vulnerabilities faced by small-scale fishers and farmers of the Yucatan Peninsula

within their territorial circuits of production-consumption, due to rules imposed

by the global food regime.

|

TPCC link

|

Key vulnerabilities

|

|

Artisanal fishers

|

Small-scale farmers

|

|

Extraction / Production

|

Overexploitation of resources; illegal fishing; lack of generational replacement;

blue dispossession.

|

Dependence on industrial inputs; soil depletion; low yields; production losses; lack

of generational replacement; green dispossession.

|

|

2. Storage

|

Lack of household and community infrastructure; catch losses due to the highly perishable

nature of the resources.

|

Lack of household and community infrastructure; loss of harvests.

|

|

3. Processing

|

Abandonment of food preservation and transformation processes for seafood products.

|

Low levels of the processing skills required for extending shelf life and adding value

to foodstuffs.

|

|

4. Distribution

|

Private monopolization of transport capacity at scale, imposing high freight rates;

relatively high export and concentration of marketing to the large regional tourism

sector; low direct sales to consumers and no public procurement of production.

|

Low transport capacity; high freight rates; lack of knowledge of market prices; voracious

coyotage and commercial concentration of production; few direct sales to consumers

and no public procurement of production.

|

|

5. Consumption

|

Generally low purchasing power; Westernized diets; relative loss of local gastronomy;

erosion of food reciprocity; lack of associative figures for social supply.

|

Low purchasing power; westernized diets; relative loss of local gastronomy; erosion

of food reciprocity; no associative figures for social supply.

|

|

6. Waste

|

Discarded catch; food waste; low capacities for utilization of special handling waste;

environmental contamination and sanitary problems.

|

Food waste; human and environmental contamination from chemical residues and burning

of agricultural waste.

|

The artisanal fishing sector has various distribution and marketing strategies for

species of high economic value (e.g., lobster and octopus), which are sold in several

tourist centers of the region (e.g., Cancun, Playa del Carmen), as well as exported

to markets in Europe, Asia and the United States (Coronado et al. 2020). However, products of medium and low economic value (several species of bony fish)

face market problems. There was a marketing crisis during the confinement periods

of the coronavirus pandemic, from March to July 2020 (Cobi 2020). On the other hand, the fishers have few strategies to market their lower value

catches to non-coastal rural communities, where the diet of middle and low-income

people includes almost no fish (Becerril 2013). In this sense, the problem of commercialization and markets for fish products also

negatively affects the equitable distribution of the food and nutritional benefits

of fish (sensuAlcocer-Flores 2015) among the regional population, particularly those suffering from health and nutrition

problems, which are largely those of middle and low income.

On the other hand, the agricultural systems of the Mayan farmer’s communities in the

YP revolve around four central production units: the milpa, the forest, home gardens and cash-crop plots. Particularly in communities that continue

to practice agriculture with traditional features, planting of the milpa is combined with the harvesting of the forests based on an agroforestry-type management

scheme. Home gardens are backyard areas surrounding Maya houses that contain cultivated

plants, animals and infrastructure are worked by the families themselves. Therefore

they represent multifunctional agroecosystems of agricultural, forestry and livestock.

Finally, in addition to the millenary agroforestry systems described above, government

programs in several rural regions of the YP from the 1960s and 1970s onwards promoted

irrigation production schemes for the commercialization of around 60 fruit and vegetable

species in regional tourist, national and international markets (Lazos et al. 2022).

The main problems of the agricultural sector are productive, commercial, and food,

which encompasses six main links of the TPCC circuit (Table 1). Above all, since the 1980s and 1990s, under public programs for the modernization

of rural Mexico, milpa agriculture began to undergo a process of simplification due to increasing use of

agro-industrial inputs. The simplification of the milpa has reached the extremes of hybrid maize monoculture (or bicultivation with beans)

with the use of herbicides, pesticides, fungicides and chemical fertilizers, which

is causing problems of soil fertility loss, soil and groundwater contamination, reduced

agrodiversity, and abandonment of fallow land, among others. In commercial terms,

the agricultural production regularly faces very low distribution capacities and,

consequently, prices that are severely manipulated by voracious regional intermediaries.

Most of the international arrangements for commercialization of citrus fruits collapsed

decades ago and, during the sanitary contingency, historic low prices were recorded

for most citrus fruits, vegetables, as well as maize and honey (Lazos et al. 2022). The low prices made the harvest of the crops themselves unviable, and significant

food waste occurred due to the abandonment of production in the plots. It is also

important to note that farmers tend to recurrently report annual seasons of undernourishment,

especially during the renewal months of the agricultural cycle when the production

of basic self-sufficiency crops from the previous year begins to run out. In general

terms, as indicated in the introduction, fishers and farmers in the YP have both been

experiencing a process of transition from their traditional diets towards western

consumption models of ultra-processed products with high intakes of saturated fats

and refined sugars and low intakes of fiber and vitamins.

Expected results

The first expected output would be a list of the species that make up the fishery

and agricultural products produced by the systems under study. The second output,

which is considered key for this type of study, is a participatory mapping of TPCC

bottlenecks and innovation niches in which the transdisciplinary team establishes

multi-stakeholder alliances and the mobilization of actions that could be leveraged

to begin the transition towards fairer and relocated food systems (Figure 4). It is expected that the map obtained will also be presented to the rest of the

social actors that form the nodes of the study area (processors-distributors, marketers

and consumers) for their information and feedback. Based on their analysis and contributions,

they will have proposals for new practices that can be complementary to the alternatives

proposed by the small-scale producers. As examples of new practices related to food

systems that have taken place in different Mexican territories, the following four

major niches of territorial innovation that could arise in the methodological case

in question are listed below:

-

Implementation of a regional food relocation action plan: based on food complementarity

between coastal and inland areas, as well as proximity access for urban and peri-urban

popular sectors.

-

Development of a lobbying agenda for national and international funds, as well as

regional alliances: to expand local storage and processing capacities for fishery

and agricultural products and promote new production mobility schemes that include

the acquisition of community means of transportation, as well as chartering and solidarity

intermediation systems.

-

Holding of a series of workshops aimed at promoting food culture and nutritional

health: based on the consumption of regionally produced fish and agricultural foods

and the recovery of local gastronomies.

-

Promotion of social economy schemes: to encourage the emergence of associative figures

of production, consumption, savings and loans that favor the supply of food within

local livelihoods.

Figure 4

Participatory mapping of opportunities for niche innovation in the local food system

based on the establishment of synergies between actors in the territorial production-consumption

circuit.

Source: Own authorship.

Challenges and limitations of the proposal

A first possible obstacle to carrying out the proposal is financial, given that adequate

funding must be sought for it. We also agree with the proposal of García-Barrios (2019, 10), who states that the potential obstacles in any Mexican and Latin American research

and transformation project, such as the one presented here, could be of three types:

“1) The obstacles to design and build the appropriate intervention instruments; 2)

the obstacles to form the social subjects willing and able to transform the situation;

and, 3) the obstacles (legal, ethical, cultural, etc.) to transform the field of action.”

To point 2, it should be added that “Such cooperation should be led by well-organized

regional communities” (García-Barrios 2019, 9). In the Mexican case, this implies a problem because the neoliberal governments

of past periods implemented subsidy programs of a welfare nature, which accustomed

many communities to be passive and not to exercise their own initiative in seeking

local solutions to their productive problems. This represents a challenge for research

and transformation projects, especially for the Mexican fishing sector, where some

small-scale fishers have recently informed us that their sector suffers from considerable

organizational problems (see also Cisneros-Mata et al. 2023).

One of the most important obstacles could be of an economic-political nature. For

example, we foresee that, once the RIT collect the data of the social and commercial

subjects that form the map of the current TPCC circuits of fish and agricultural products,

it will also become known which of them have more economic and political power. That

is, more decision-making power over the structure and function of the studied circuit

in the fishing sector; as researchers did in the TPCC circuit of octopus (Coronado et al. 2020), as well for beef in the peasant farming sector studied by Rivera-Núñez et al. (2020). Our expectation is, as has been seen in other territorial TPCC circuits in Mexico

and Latin America, that those with the greatest economic-political power will be the

social subjects of the group of entrepreneurs, who generally have the support of the

authorities such that, as a whole, they are referred to as the economic-political

group; while those with less power will be the small-scale fishers and farmers themselves

(Bello-Baltazar et al. 2020; Coronado et al. 2020). A possible constraint to any transformation of the status quo will therefore be whether the balance of power would allow the new practices or innovation

niches proposed by small-scale producers in the territorial TPCC circuits to be carried

out.

Concluding remarks

The exclusion processes of the global food regime for small-scale fishers and farmers

in Mexico can be approached from several perspectives. The present study used our

context-specific transdisciplinary experience, which derives from almost three decades

of working closely with local communities, civil organizations, government agencies

and research groups in the Yucatan Peninsula. Consequently, we have identified that

the complex processes of exclusion of the global food regime act under a structuring

process of neoliberalism where, to date, there has been a gradual dismantling of Mexican

fishing and agricultural means of production, commercial organization and food sovereignty.

Such productive, commercial and food dismantling is the result of how the nation-State

respond to the logics of global agreements known as “conditionality lending” (De Moerloose 2014; Vordtriede 2019, 1), where signatory countries, like Mexico, modify their laws and carry out structural

reforms following a development agenda dictated by the financial institutions that

grant them the loans. The conditionality lending encompassing modification of national

laws together with structural reforms has been taking place in other Latin American

countries as well, including Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Cuba, Colombia, and Honduras

(Bello-Baltazar et al. 2020). In the case analyzed in our study, since small-scale producers are at the bottom

of the market linkage, they present precarious income conditions and very little maneuverability

in terms of their commercial process in regional and national markets. As a result,

many coastal and agricultural communities tend towards food insecurity. In relation

to this problem, we do not consider that the Mexican government has the full capacity

to maneuver in the short term to help these food systems and rural producers to improve

their situation. Our proposed transdisciplinary approach is therefore based on the

argument that collaboration between social subjects of the LSES, mainly between the

group of producers and academia, is fundamental in order to reverse the conditions

of vulnerability imposed by global food regimes in those territories without explicit

manifestations of social mobilization (Herrera and Guerrero-Jiménez 2020). Other actors, such as thoughtful consumers and solidarity intermediaries, must

play a central role in collaborating to construct new local commercial networks or

nested markets (Van der Ploeg et al 2022) and a place-based food culture, given the lack of localized scope of public policies.

In this collaboration, mainly fishers and farmers will make use of their visions to

identify and enable innovation niches, in such a way that will allow them to articulate

in complementary TPCC circuits of fish (of medium and lower economic value) and basic

agricultural products that connect coastal areas, the rural hinterland and small and

medium-sized cities within micro or meso regional contexts.

In order to confront the food regime, beyond prescribing some of the demarcated ideological

and mobilizing positions that have already figured in the heated international food

debate (such as food security, food sovereignty, food self-sufficiency, the right

to food, food autonomy, among others), we have chosen to outline those operational

features that can lead to the relocation of the food systems. In our bid for food

relocation, the complementarities between fishing and farmer communities, as well

as between small and medium cities play a central role, due to the geographical proximity

of less than 200 km between coastal and inland areas that occurs in the Yucatan Peninsula,

as well as in many regional contexts of the country, mainly in the west, south-southeast

and Gulf of Mexico. It is possible to put into practice the transdisciplinary proposal

outlined in this work, because during the COVID-19 sanitary contingency we witnessed

the solidarity food complementarities between small-scale fishing and farming families

in contiguous communities, as well as the emergence of alternative food supply networks

in the cities and in rur-urban areas of the Yucatan Peninsula. Lastly, we consider

that this proposal is broadly flexible for use in multiple contexts that share the

fishing, agricultural and popular consumer proximity, mainly in the Global South and

with some focus on the Latin American region.